People often ask me why the market, or some segment of it, has been acting the way it has been recently. My go-to response is usually something along the lines of “Well, the market is a chaotic system made up of the decisions of billions of people around the world, whose motives are often not even explicable to themselves, much less to me, so there’s really no telling why the market does anything in particular.” Usually after I’ve given this answer two or three times the person learns to stop asking me.

But then there are times when the market is not so mysterious, when it’s perfectly clear just what the market is reacting to. March 1st of this year was one of those days.

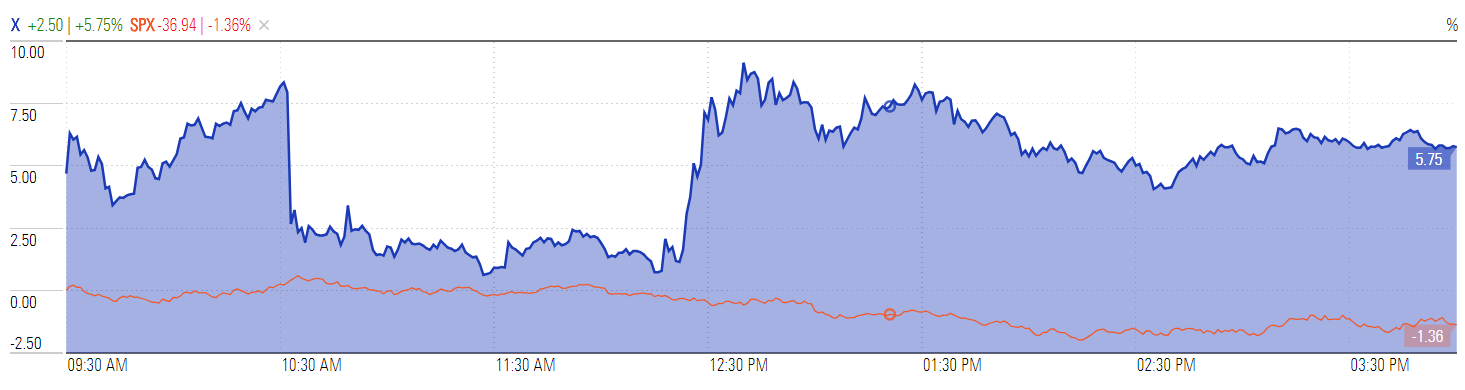

Early on March 1st, news broke that President Trump had summoned executives from the US steel and aluminum industries to the White House on short notice and it looked likely that he would soon be announcing plans to impose tariffs on imported metals. US steel and aluminum producers rallied at the market open on the news while the rest of the market fell slightly. Then around 10:30 am EST the White House, looking to nip rumors in the bud, announced that there would be no announcement regarding tariffs. The metals industry quickly shed most of its daily gains on this bit of anti-news, while the S&P 500 clawed its way back into positive territory. Just a couple hours later, Trump, contradicting the earlier statement, announced he would soon be imposing 25% and 10% tariffs on imported steel and aluminum, respectively. The metals industry immediately rallied back again to its earlier highs while the rest of the market sank. Below I plot the roller coaster performance of United States Steel (X) – America’s largest steel producer – for the day, against the S&P 500 (SPX).

US Steel was up over 5% for the day along with its peers, adding hundreds of millions of dollars to its market valuation as investors anticipated a US metals industry that could soon charge higher prices, protected from foreign competition. But these gains were more than offset by the billions of dollars in valuation lost by major consumers of steel and aluminum, such as Ford and Boeing, each of which was down over 3% for the day. Overall, the US market fell about one and a half percent on the news, with the rest of the world following suit.

In the months since, Trump has gone back and forth on the issue, taking the market and the international community with him. Originally slated as applying to all countries, Trump then drew up a list of allies who would be excepted from the tariffs at the behest of top advisors. Then, on May 31st, Trump changed his mind again and announced the tariffs would indeed be applied to Canada, Mexico, and the European Union. Again, US metals manufacturers surged on the news while the rest of the global market slumped.

The response from the economics and finance community has been one of predictable and universal opposition. Ever since Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations in 1776, if there’s one thing the economics profession can agree on it’s that free trade benefits all nations. A University of Chicago survey of economists across the country found unanimous consensus that the tariffs would not benefit Americans, and many top executives at major financial institutions like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have come out against the new tariffs.

But while the mainstream press focuses on the economic and political ramifications of this escalating conflict over trade, I want to make a somewhat different point: while the financial industry has voiced its disapproval of this rising tide of protectionism, nonetheless the fact that we’ve gotten here in the first place represents, at least in part, a failure of the financial industry to perform its essential function of efficiently allocating capital across the economy. Let me explain.

For over two hundred years economists have been fighting for free trade, and for over two hundred years economists have been collectively screaming into their pillows every time politicians worldwide pass some new measure curtailing the flow of goods and services across borders. But given how universally opposed to tariffs and trade restrictions are those whose job it is to understand how the economy works, why is this such a perennial controversy? While blaming your country’s problems on foreigners has always been a universally popular political tactic, most citizens are not usually clamoring for more tariffs. Trade policy is boring as far as most people are concerned, and the discussion is usually being mostly held by political and economic elites. Trump was somewhat unusual in this regard in making trade one of his major platform issues, holding the view that the trade practices of other nations are unfair to America.

Economists have a ready-made answer to this question of why protectionism springs eternal, and it goes by the catch phrase of “concentrated benefits and diffuse costs” and is a centerpiece to an entire subfield of economics that analyzes political decision-making known as public choice theory. Whereas the American founding fathers worried that in a democratic form of government the majority would tyrannize the minority, public choice theorists claim that in many cases, especially regarding economic policy, it’s actually the opposite problem that’s the greater concern. The problem arises from this tension: as consumers we buy goods and services from a large and varied number of sellers and so benefit from free and open competition among them, but as producers we usually only earn our income from one firm in one industry, and so potentially stand to benefit if our livelihood could be protected from competition. Producers therefore always have an incentive to lobby the government for special protections for themselves, such as by shutting out foreign competitors, which allows them to charge higher prices to their customers. But as consumers, any one industry typically represents only a small portion of our expenditures, so there is not nearly as strong an incentive to lobby for more competitive markets in it. If, for example, the sugar industry can convince the government to pass tariffs and other measures that raise the price of sugar by just 15 cents per pound, that translates into many billions of dollars in extra annual revenues for a small number of firms in that business, but the average American spends only a few dollars extra at the grocery store each year as a result and so doesn’t even notice. The benefits are concentrated while the costs are diffuse, and so the political advocacy and lobbying will always be lopsided in favor of the protectionists. Repeat this process across a thousand different industries and we end up with a byzantine web of taxes, tariffs, laws, and regulations, no single one of which is all that significant, but whose combined weight makes all of us poorer.

I think this phenomenon explains a great deal of the bad economic policy we see in the world, but as a theory it’s still incomplete because it ignores one important detail, a detail that contains within it the potential for the solution to this centuries-old conundrum: the existence of public equity markets.

Corporations exist in order to maximize the wealth of their shareholders. At least, this is the mainstream view among economists and is officially enshrined in corporate law. Critics of the “shareholder value” approach to corporate management claim that focusing exclusively on maximizing shareholder value causes corporations to boost profits at the expense of the larger community or environment, and often propose alternative “stakeholder value” approaches. But this criticism is a bit of a straw man that constrains itself to too narrow a conception of what “maximizing shareholder value” actually entails. Unfortunately, many corporate executives themselves seem to hold too narrow of a view, thinking what’s good for them must be what’s good for their shareholders. And so many corporations allocate shareholders’ capital to lobbying the government for special treatment, such as the US steel industry, which spends millions of dollars every year lobbying for the sort of protections which they received this year in spades.

Now, one might argue, and perhaps the steel executives would, that this was money well spent and the managements of these companies are acting as good stewards of their shareholders’ capital; it worked after all! These steel companies’ share prices are up thanks to the protectionism they had been petitioning for. But this is a gross perversion of the concept of shareholder value. That United States Steel’s stock price went up on news of the tariffs may have benefited a hypothetical shareholder whose entire wealth and economic livelihood was tied to the price of United States Steel shares, but such a shareholder does not in fact exist. In reality, shareholders in United States Steel are also shareholders in thousands of other companies, and so news of the tariffs actually hurt investors in United States Steel as evidenced by the fact that the market was down on March 1st. This is not mere theorizing on my part, but publicly available information. If we check out the 13-F filings for United States Steel, for example, we see that the company’s largest shareholder, with 8.7% of total share held, is the Vanguard Group, the gargantuan asset manager whose hugely popular low-cost index funds are probably a big part of your 401(k) plan. Other top shareholders are all the usual suspects: BlackRock, State Street, Goldman Sachs, and other major asset managers that investors like you and me rely upon to get efficient access to the capital markets. If we look at the top 20 funds holding United States Steel stock, every one of them lost money on March 1st. The lobbying efforts of the steel industry did not help steel industry investors; it provably cost them billions of dollars.

United States Steel is by no means unusual in this regard, but is the norm. In modern financial markets, virtually all publicly traded companies are held mostly by diversified investors who also hold virtually all of the rest of the world’s publicly traded companies. When corporate executives conceive of their shareholder whose value they seek to maximize then, the only truly rational and consistent model is of shareholder as representative agent, who proxies the entirety of the global capital markets. Viewed through this lens, a corporation should only maximize its own profits in a way that is consistent with supporting the rest of the market in aggregate as well, or at least doesn’t hurt it. On the other side of the coin, it is in shareholders’ best interests to ensure that the executives who manage the companies they own operate on a level playing field in an open and competitive market, as protections that favor one industry over another merely rob Peter to pay Paul (while the lawyers and the lobbyists each take their cut). I think of this as the Golden Rule of capitalism: act so as to maximize your profit in a way that is consistent with everyone else maximizing their own profits.

Regular readers of mine will know that I have a rather ambitious view on the proper scope of finance. If necessary, the financial industry can and should save the world, if for no other reason than that our world is a very profitable place to do business. (If Elon Musk gets his way maybe one day there will be a Martian economy and then investors will finally be able to add some planetary diversification to their portfolios. But until then we all have a highly concentrated position in Earth.) Last year I wrote about how it was rational for profit-maximizing financial institutions to use their power as shareholders to force carbon-intensive companies to adopt greener policies in order to mitigate the risks of climate change, and I applauded early efforts by BlackRock and other major asset managers to do just that. Already these initiatives have won concessions from some major oil & gas companies.

I see the problem of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs, of special interest lobbying, as the next vista of corporate governance reform that the financial industry should take up. Investors should not tolerate corporate managers who spend millions of dollars lobbying the government for favors at shareholders’ (and the rest of society’s) expense. It’s time for capitalists to stand up to defend free markets and free trade for all.

Disclosures: This post is solely for informational purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Investing involves risk and possible loss of principal capital. No advice may be rendered by RHS Financial, LLC unless a client service agreement is in place. Please contact us at your earliest convenience with any questions regarding the content of this post. For actual results that are compared to an index, all material facts relevant to the comparison are disclosed herein and reflect the deduction of advisory fees, brokerage and other commissions and any other expenses paid by RHS Financial, LLC’s clients. An index is a hypothetical portfolio of securities representing a particular market or a segment of it used as indicator of the change in the securities market. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur fees and expenses and cannot be invested in directly.