In my last post, I gave my two cents on the old investing debate of whether real estate or the stock market is the better investment. I concluded that real estate (particularly residential housing) is roughly just as risky as stocks are, earns somewhat lower returns than stocks do (at least after adjustments for capital expenditures and quality adjustments are made), is much more difficult to diversify, is subject to many more hidden fees and taxes, and is much less liquid and generally just much more of a pain in the neck to deal with than publicly traded investments like stocks. Most investors, therefore, should probably wish to hold more of their investment capital in stocks than in houses. But the decision to be a landlord vs. a stockholder is a dilemma faced mostly only by relatively wealthy investors. Everyone, on the other hand, has to live somewhere, and in most times and places, homeownership is well within the reach of the middle class. So for most people, the more relevant financial decision to make – indeed one of the most important financial decisions most people do make – is whether to rent or buy their home.

The conventional wisdom here falls squarely in the “Buy” camp. Buying a house and paying a mortgage is just one of those things, like getting married and having 2.5 kids and paying your taxes, that most people just sort of expect normal, responsible adults do, and is typically one of the foremost financial aspirations of young adults who are still renting. Young renters often feel (and are often encouraged to feel by their parents) that they are just “throwing money away” every time they write another check to their landlord. And it’s not too hard to see why if you’re capable of doing some simple arithmetic. Sure, buying a house costs more money up front, but if you consider the simple case of a house you buy and live in for the rest of your life versus renting, and just add up all the dollars spent over the years, buying a house is going to seem like the clear winner. Over time you’ll build equity in the house you buy and eventually you’ll own it “free and clear” and not have to make payments anymore (besides, you know, property taxes and maintenance); meanwhile your loser friends down the street are still renting and making monthly payments well into their golden years like some suckers. You don’t want to be a sucker, do you? So buy a house!

Interrogating Common Sense on Rent vs Buy

As you have probably guessed, I am skeptical of the conventional wisdom on this topic. The conventional thinking here is that buying a house is almost always a “good deal” compared to renting. Economists, on the other hand, hold as a general view of the world that “good deals” are hard to find, especially when trillions of dollars are at stake, as is the case in the housing market. Economists believe that in open and competitive markets prices are “fair” in the sense that they don’t obviously favor one side of the market or another. In the housing market, this means that a priori we should expect that for the typical person the financial cost of renting versus buying a house to be approximately equal. If owning a home were the obviously better deal, people would bid up the prices of homes, and demand for rentals would fall, such that the price-to-rent ratio would rise until it became more attractive for people to rent again. And we could imagine the same scenario in reverse if renting were obviously better.

So economists theorize that people ought to be indifferent between renting and buying, but how would we know if this is correct, and how would we know if we’re a “typical person” anyway? Renting a house is a very different kind of transaction than buying a house, and every house and every person is different and faces different financial circumstances. How do we compare these apples and oranges?

There are all sorts of “Rent vs Buy Calculators” available online that will try to do this for you. They generally ask for a few key variables like the price of your house, rental cost, and mortgage rate and try to show you which is the more economical decision. Many of them express this in terms of a breakeven time frame, i.e. how long it will take before the total costs of buying are lower than the costs of renting. What you’ll often find with most of these calculators is that they seem to confirm the conventional wisdom, that buying is generally cheaper than renting if you plan to live in your house more than just a few years. But that is because most of these calculators are extremely bad because they underestimate or just completely ignore the most important cost associated with buying a home, one that many homeowners fail to consider entirely: opportunity cost. The large upfront costs of buying a house have to come from somewhere, presumably the home-buyer’s savings and investments. If it weren’t locked up in the house, this money could continue to earn returns for the potential buyer if he chose to continue renting instead. While buying a house will almost certainly mean fewer dollars spent on housing over the course of a lifetime, it will also mean fewer dollars earned on non-housing investments. This opportunity cost, the difference between the return offered on houses versus the return offered on say, stocks, is actually the most important cost to consider when purchasing a home, and as we will see can have a dramatic effect on how economical we calculate homeownership to really be.

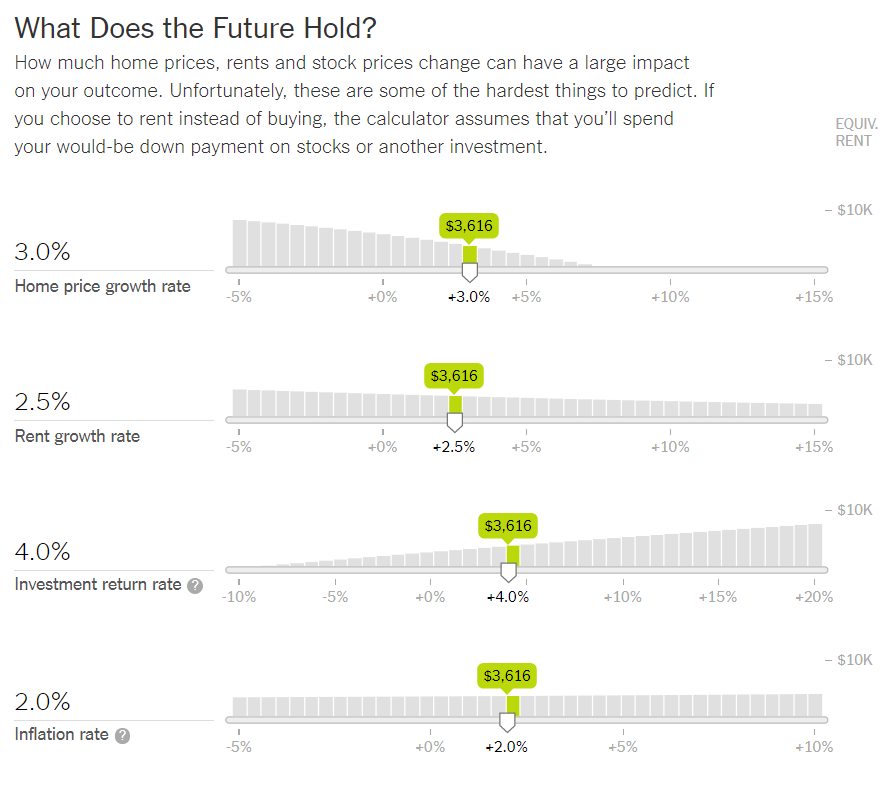

For this reason, my favorite online rent vs. buy calculator is this one by the New York Times. The NYT calculator expresses its answer in terms of a rental equivalent, as opposed to a breakeven time frame, stating “if you can rent a similar home for less than X then renting is better.” It takes a detailed account of all the relevant financial inputs such as home price, mortgage rate and term, taxes, closing costs, and, most importantly for our purposes, assumptions for home and rent price appreciation and investment returns. I’ll use my own house as an example. According to Zillow, my house (which I rent) in the Excelsior neighborhood of San Francisco is worth $1,118,407 as of May 2019, with a monthly rental value of $4,150, which is indeed close to what I actually pay. Plugging my home value into the calculator and leaving all the other inputs at their default setting yields a breakeven rental cost of $3,616. Since this is less than I actually pay in rent I’m better off buying my house from my landlady, right?

Not so fast, let’s look under the hood here. Here is the section the NYT uses for calculating opportunity costs, with the settings at their defaults:

These assumptions are in line with ones I’ve seen elsewhere, but they represent a view of the world through heavily-tinted realtor glasses. First of all, the assumption that housing prices should appreciate faster than rents over the long run is patently absurd; eventually, that would lead to a world where it was obviously cheaper to be a renter than a buyer. Now, this has been the case over the last couple of decades, especially in major coastal cities, but in the long run it’s clear that these two numbers have to be equal to each other, or else we end up in a world where landlords are paying millions of times more for houses than they can get by renting them out. In equilibrium, rents and prices must go up by equal amounts.

These assumptions are in line with ones I’ve seen elsewhere, but they represent a view of the world through heavily-tinted realtor glasses. First of all, the assumption that housing prices should appreciate faster than rents over the long run is patently absurd; eventually, that would lead to a world where it was obviously cheaper to be a renter than a buyer. Now, this has been the case over the last couple of decades, especially in major coastal cities, but in the long run it’s clear that these two numbers have to be equal to each other, or else we end up in a world where landlords are paying millions of times more for houses than they can get by renting them out. In equilibrium, rents and prices must go up by equal amounts.

How much should they go up by? The assumption that housing prices will rise 1% faster than underlying inflation is dubious. Here’s a chart I’ve shown a few times before, US average housing prices after inflation since 1890:

Source: Robert Shiller’s Online Data

The average annual return after inflation on a typical house in the US over the last 130 years was 0.43%. For the first 110 years or so of this sample, it was basically zero. Then, around the turn of the millennium, everybody went crazy for a little while and became a real estate agent (my own mother included) and drove the real prices of houses up to roughly double their historically normal values. Then we had a big crash about a decade ago and everybody was sad for a while. And now we’re once again back up close to where things were in the last housing bubble, only this time it’s not being driven by my mom but by foreign – especially Chinese – buyers. My point is the last twenty years have been kind of a weird time for real estate and we shouldn’t anchor our expectations on them too heavily. The safer, more conservative assumption is that in the long run real estate simply keeps up with inflation. Even this might be too high; as I pointed out last time Credit Suisse found in a recent research report that after adjusting for the capital expenditures necessary to keep a house up, the real price of houses around the world has fallen by 2.1% annually over the last century.

Let’s just set rent and housing price growth equal to the 2% inflation rate for now. This raises my breakeven rental equivalent up to $4,464, slightly more than I’m already paying! So you can see how even small differences in assumptions about rates of return can have a dramatic impact on the rent vs buy calculation. Just making a slightly more realistic assumption about housing price growth changes my situation from being better off buying to better off renting.

But we haven’t even adjusted the most important knob yet, the investment return rate, our opportunity cost for tying capital up in housing. The NYT calculator has this set to 4.0%. This is overly conservative, in my view. A globally diversified portfolio of stocks has earned roughly 6% above inflation, historically, and I expect will likely continue to earn something close to that. Investors willing and able to avail themselves to some of the strategies I write about on this blog, such as leverage and contrarian investing, may reasonably expect to earn a few extra percentage points off their portfolios over the long run, though of course, we should be careful not to become overconfident in our investment acumen. Let’s use an 8.0% investment return rate for now. This raises my breakeven rental rate in the calculator to $5,411, way more than I’m paying now. Based on these assumptions, I’m much better off financially continuing to rent as opposed to buying a comparable property, by over $1,000/month.

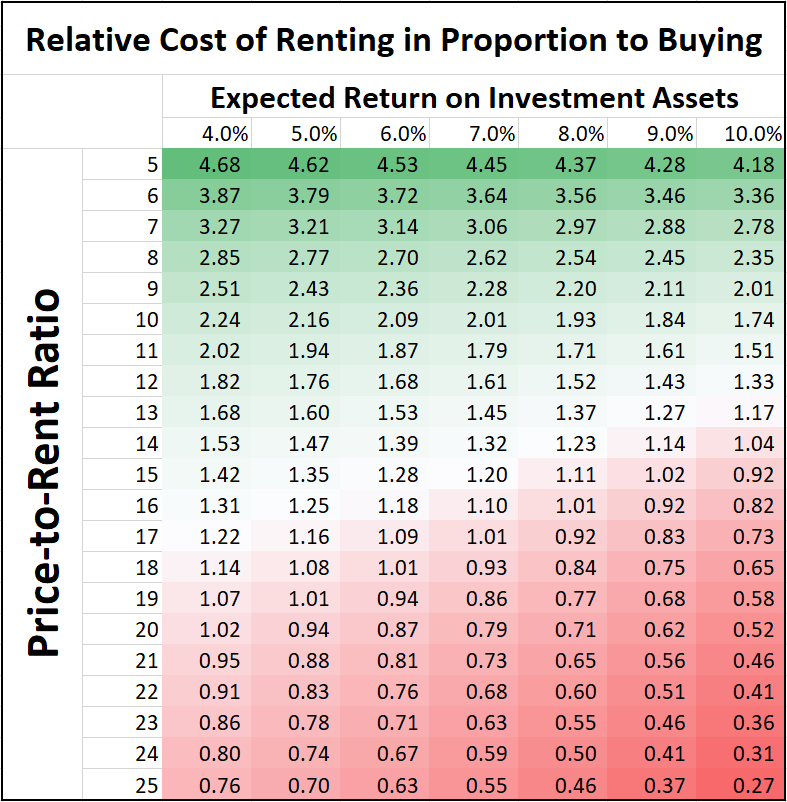

How generalize-able is my case? I live in San Francisco, where housing prices are famously insane. I would encourage anybody who is considering purchasing a home to play with the NYT calculator using their own numbers and see what they find. Your answer will ultimately depend on a number of factors that are unique to you, such as your marginal tax rate, how long you plan to live in your house, what the property taxes in your area are, etc. But the three main objective financial variables that determine the relative attractiveness of renting versus buying are the prices of homes relative to their rental rates (the price-to-rent ratio), the expected return on investment assets, and the cost of your mortgage. Mortgages right now are being offered at about 4% APR. Let’s use that figure, along with all the other default numbers in the NYT calculator, and figure out how much more or less expensive it is for somebody to buy versus rent a house as a function of the price-to-rent ratio and the investment expected return, assuming they live in their house 10 years and have a standard 30 year fixed mortgage with a 20% down payment.

Below I plot how much it costs to rent a house as a proportion of the cost of buying a house of the same value, for different values of price-to-rent ratio and expected return. The costs being calculated here are the explicit costs of housing (rents, mortgage payments, repairs) less the benefits received (either from housing price appreciation or appreciation of investment assets). A value of one indicates parity: renting costs the same as buying. Values less than one indicate renting is cheaper; a value of 0.5 indicates the renter spends half as much as the buyer over ten years. Values greater than one mean the opposite: renting is more expensive than buying. A value of 2 indicates the renter spends twice as much as the buyer over ten years.

As you can see, depending on the price of housing relative to rent and the return assumptions used, there’s wide variation in the rent versus buy calculation. For aggressive investors looking at properties in expensive parts of the country (like me), renting is barely one quarter the cost of buying a house. On the other hand, conservative investors looking at houses in very inexpensive parts of the country will find the reciprocal: renting is four times more expensive than buying or more. Looking at the breakeven points, using the in-my-opinion-too-conservative default NYT expected return figure of 4%, buying a house is cheaper when the price-to-rent ratio is about 20 or less. More than 20 and renting is cheaper. For the 8% expected return figure reflective of long-term equity returns, the breakeven price-to-rent point is lower at about 15. Again, this is all assuming a mortgage rate of 4%. We could imagine expanding this grid into 3 dimensions with mortgage APR on the third axis (lower mortgage rates make the attractiveness of buying relative to renting higher, all else equal). I leave this as an exercise to the reader.

These price-to-rent ratios, by the way, roughly span the range that’s currently available in the United States. According to Zillow, the most relatively expensive metropolitan market right now is San Jose, California, with an eye-popping price-to-rent ratio of 27.7. Second is Honolulu at 22.6 and third is my home of San Francisco at 21.9. For sky-high markets like these, renting is cheaper than buying under almost all scenarios. On the other end of the spectrum you have some, err… quieter towns like Vernon, Texas with a price-to-rent at 4.9 or Malone, New York at 5.1, where buying is clearly much more economical. Across the US, the average ratio right now is only 12.3: pretty reasonable. But in most of the major coastal cities, the ratios are in the high teens to low 20s.

Risk and Other Considerations

Some people may say it’s apples and oranges to compare stock market returns to the housing market and it’s too aggressive to do so. To such people I say: nuh uh, houses are actually a lot riskier than you’re giving them credit for, and it’s perfectly reasonable to compare them to the stock market. As I explained in detail in my last post, while housing and other private real estate index data naively suggest that these markets have only a fraction the volatility of equities, when we correct for reporting and other sample biases we see housing volatility is substantially greater than it first appears, and the volatility of individual houses (as opposed to city or country-level aggregates) is perhaps twice that. Then you add in the fact that most home-buyers start off with at least 5 to 1 leverage (i.e. 20% down payment) on this already risky asset, and then to top it off you add in the fact that the value of the home is highly correlated with the local economy and therefore the local job market, meaning that as the price falls, so too does the probability that the homeowner will be able to keep up with her mortgage payments.

In fact, for especially this last reason I would say that particularly for younger people still relatively early in their career (generally less than 40 or so), buying a house is much riskier than investing a comparable amount in the stock market. The reason is that when a recession hits, junior employees are usually the first ones let go, so younger people usually face the most job risk. If this happens to you, you may find that the best place to get back on your feet is not wherever you currently live, but maybe in another city. If you own a house, however, and especially if you’re underwater with your mortgage, you may find that you don’t have the flexibility to move if necessary. This is exactly what happened in the Great Recession. While historically economic dislocation has been a great cause for geographic mobility in our country, when the last housing bubble burst we saw a decline in interstate moving as many underwater homeowners couldn’t afford to move, even if they would have been able to find a better job elsewhere. Renting offers more flexibility than owning in this regard, and this flexibility is especially valuable to younger people.

On the other hand, older people face the opposite dilemma. If you are in or close to retirement, the local job market probably doesn’t personally concern you much. What does concern you is getting priced out of the market, and if you are renting you risk facing increasing rents that squeeze at your limited resources. For this reason, homeownership is probably less risky than renting for most seniors.

On the subject of economic cycles, another consideration rarely discussed is that in the housing market the old investing maxim “buy low sell high” makes even more sense than it does in the stock market. While it’s generally a very bad idea to make big all-or-nothing decisions about getting into or out of the stock market based on one’s forecast of the next recession, the logic is different with housing. This is because in the housing market renting is a generally very economical alternative to buying, a situation in which the stock market has no analogous opportunities. So my advice to first-time home-buyers (or even just those looking to upgrade) is this: wait until the next recession to buy your house. In the depths of a recession, housing prices will almost certainly be cheaper, and mortgage interest rates will be lower as well. True, lending standards are also stricter, but you should only ever take out a mortgage you are solidly over-qualified for anyway. The bank doesn’t want to lose money on your mortgage, but if they do you’re just a drop in the bucket. For you though, your house and your mortgage may very well be the entire bucket, so the credit standards you apply to yourself should be more prudent than the bank’s. Waiting til the next recession to buy a house can potentially save you hundreds of thousands of dollars or more over the course of your life, but more often we see the opposite behavior. It’s when the economy is doing well and everybody is making money that people start feeling like money is burning a hole in their pocket and they have to spend it on the biggest house they can afford so they can keep up with the Jones’s. I’ve had several conversations in the last year or so in the Bay Area with peers of mine where they express interest in buying a house in the near future and when I ask them why they often say something like, “well everybody else is doing it and I don’t want to miss out before prices go even higher.” Everybody, buying a house because everybody else is doing it is the opposite of a good reason to buy a house! Financial FOMO is the most common cause of economic ruin, a lesson millions of Americans learned the hard way in the last housing bubble, and one I fear we may be getting a review course in before very long.

So, potential home-buyers of the world: be informed! Do your homework! For too long our culture has fostered the notion that homeownership is synonymous with prudence and responsibility and that renting is a waste of money that adults should avoid as soon as they can afford to. This attitude drove our economy off a cliff a little over a decade ago and based on what prices have been doing recently it might be happening yet again. The truth is more nuanced. Home-ownership is much riskier than is commonly acknowledged, and renting is much cheaper than most people realize, once we properly account for opportunity cost. Buying a home is often the economically wise thing to do for people doing so at reasonable prices, at an affordable mortgage rate, with a sound and steady source of income, and who plan to live there for many years. For everybody else, renting may very well be cheaper, potentially much cheaper, especially for those people living in major coastal cities, most especially California. Basically nowhere in California has “reasonable prices” right now according to my definition. So long as they remain that way I’ll be perfectly happy renting, knowing I have more money to put away into higher-returning investment assets. I encourage my fellow city-dwelling, avocado-toast-eating peers to look at it the same way.