Okay, here’s an easy one, which would you have rather owned, Asset A or Asset B?

Asset A, in this case, is the SPDR REIT ETF. Asset B is Vanguard’s Total Stock Market ETF. As you can see, over the period 2003-2015, REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts, basically stocks of companies that manage commercial real estate) outperformed the broad US stock market by a good margin, 11.2% annualized versus 9.1%.

But does that automatically mean Asset A was a better investment? The answer depends on your taxes. Because of their unique corporate structure, the dividends from REITs are treated as ordinary income for taxable investors. Since 2003, on the other hand, dividends from common stocks have generally been taxed at lower rates. For a US investor in the 35% tax bracket, the annualized after-tax return for the REIT ETF would have been about 8.4%, only slightly higher than the 8.2% after-tax return of the total stock market ETF. Once you factor in the greater risk of the REIT market, it’s no longer clearly the superior investment the graph above makes it seem.

Throughout this series, I’ve been going through the assumptions of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), the set of ideas underlying today’s index funds, and showing how they fail to describe the real world. MPT essentially assumes all investors are the same, that “beating the market” is impossible and so everybody should basically hold the same set of index funds, adjusting their asset allocation based only on their tolerance for risk. We have already gone through how in fact investors differ in whether or not they’re willing to use leverage or the degree to which they’re affected by cognitive biases, now we turn to a topic that impacts everybody differently: taxes.

Everybody knows that they have to pay taxes, and with top marginal rates over 50% in this country, it’s clear that they can have a large impact. Despite this, the importance of taxes on investment decision making is widely underappreciated, both in theory and in practice. First, the mere existence of differing tax rates implies that market-capitalization weighted portfolios cannot be optimal for all investors, undercutting the theoretical motivation behind index funds. Secondly, individual investors by and large seem to largely ignore easily-adoptable tax-minimizing practices with their portfolios, and in fact often take deliberate steps that make their investments less tax-efficient, as though paying more taxes than necessary were their patriotic duty.

Let’s first see how taxes affect market efficiency. Recall that the advocates of index funds claim that in the long run it is impossible to beat a given market – say, the US stock market – by picking and choosing from stocks within that market. Better then, to simply buy the entire market and save money on management fees. Indexing fans go further and often point out that because index funds rarely have to buy or sell securities, they typically have little to no capital gains realizations, and so are much more tax-efficient than alternatives.

But tax-efficient does not mean tax-free. Though a US stock index fund might not have much in the way of capital gains distributions, it will distribute dividends, which taxable investors will have to pay for. The dividend yield on a total US stock index is currently about 2% (low by historical standards). If the total return on the market is 6%, and an investor’s dividend tax rate is 15%, then her after-tax return will be 4% + (2% * 0.85) = 5.7%. Not bad, but less than 6%. But the stock market contains plenty of companies that don’t pay any dividends at all. One could easily imagine an “index fund” that simply excluded any dividend paying stocks. And if beating the stock market by picking certain stocks is impossible in the long run, then it follows that underperforming the market by excluding certain stocks isn’t possible in the long run either, so such a portfolio should earn the same 6% return, but without any tax liability, thus effectively beating the market for the taxable investor.

Note that you can’t escape this paradox by assuming that the expected returns for different stocks simply adjust for their respective tax liabilities, because different investors face different tax rates, and some investors (such as pensions and endowment funds) don’t pay any taxes at all. If high-yielding securities earn higher pre-tax returns to compensate for their tax burden, then low-tax-bracket and non-taxable investors can outperform the market by investing more in dividend stocks. If pre-tax returns don’t adjust based on taxes, then taxable investors can outperform the market after-tax by avoiding dividend stocks. So which one is it?

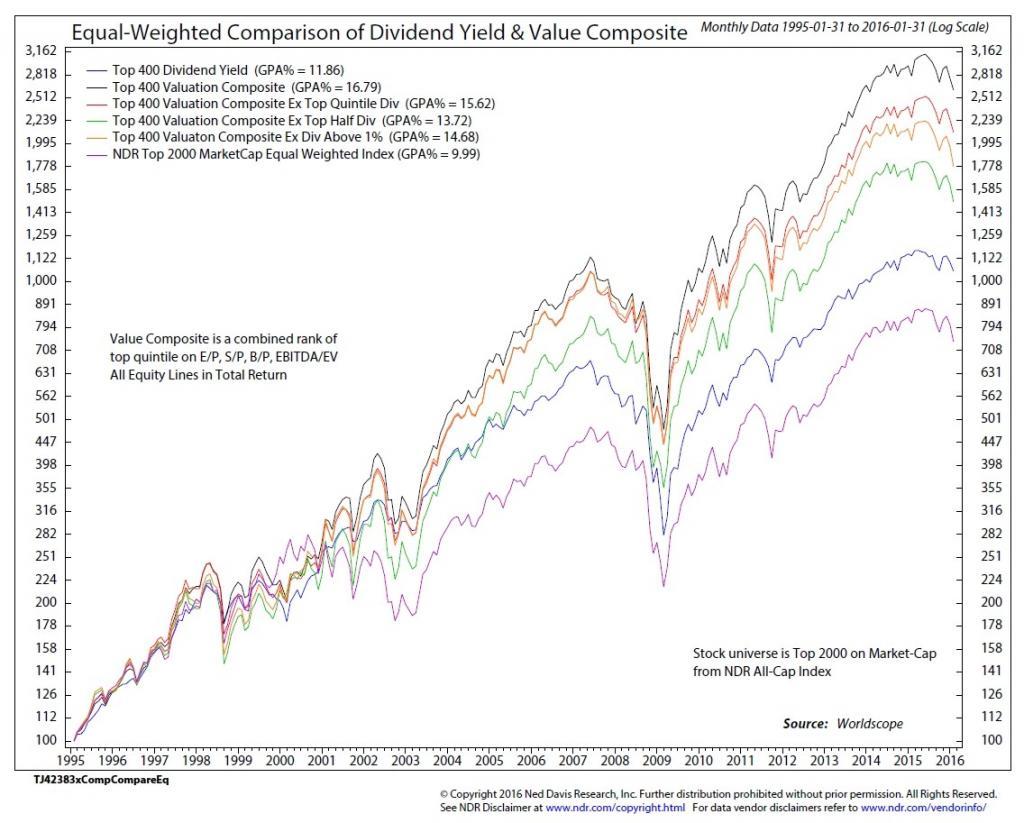

The former, it turns out. High-yielding stocks have earned more than low-yielding stocks, which have earned more than stocks that don’t pay dividends. This outperformance seems to be mostly related to the value effect, though. Another way of saying that a stock has a high dividend yield is that it’s price is low relative to its dividend, i.e. that it’s undervalued, which as we saw last time is predictive of future outperformance. That said, dividend yield is one of the weakest measures of value. Fellow finance blogger Meb Faber recently wrote about how a value strategy that excluded high-yielding stocks would have outperformed a portfolio formed on dividend yield by several percentage points pre-tax, with an additional 0.3%-1.5% benefit from reducing dividend taxes.

Unfortunately, I don’t know of any funds or ETFs that follow such a dividend-minimizing value strategy. There are, however, currently 124 mutual funds and 54 ETFs with “dividend” in their name, offering high yields and/or growing payouts. Dividend investing is popular, especially in today’s low interest rate environment, where investment income is low. Dividends seem like more of a sure thing: the cash they put in your brokerage account is real and tangible. The idea that if the company had reinvested the cash instead their stock would have appreciated by more than the amount of the dividend is hypothetical and esoteric. The tax liability associated with the dividend is just as objective, but that is only seen next April 15th.

The dichotomy between the visible and salient and the out-of-sight and out-of-mind seems to be responsible for many tax-related investment errors. Investors just don’t see their after-tax returns, and so seem to fail to consider them. A few common examples:

- I mentioned last time the disposition effect: investors are often quick to sell a stock at a gain and feel like a winner but reluctant to sell at a loss and admit defeat. This is of course exactly backwards from tax-efficient behavior. While selling an asset at a loss can reduce your taxable income, selling a winner realizes a capital gain you must pay taxes on. If you are too quick and sell within a year of buying, you’ll pay the much higher short-term capital gains rate. Following a strategy of proactively harvesting capital losses – selling losers and reinvesting into similar assets – can potentially increase after-tax returns by up to 0.8% per year, according to some simulations.

- Similar to the case of dividend yield with stocks, investors often “reach for yield” with bonds as well. The most popular bond mutual funds are “total return” and “high income” funds that invest in all manner of corporate, credit, mortgage, and other debt securities in order to juice up their yields. In this case, the attraction to yield is even less defensible: contra the higher returns earned on higher dividend-yielding stocks, higher-yielding corporate bonds have generally not outperformed treasury bonds, plus they have higher risk and tax burdens to boot. An often overlooked feature of treasury bonds is that their interest is not taxable at the state or local level, unlike corporate bonds, which are fully taxable. Elton, et. al. find that most of the difference between the yields on treasury vs. corporate bonds can be explained by this difference in tax status, plus corporate bonds greater sensitivity to the stock market (unlike treasuries, corporate bonds are more likely to go down at the same time as stocks, exactly when you least want it).

- Alternative assets often represent an expensive tax headache. As the example up top shows, the tax efficiency of common stocks can often overpower the returns on alternative assets, which are usually subject to ordinary income rates. Furthermore, though REITs don’t suffer from this, many investors receive the unwelcome surprise of discovering that many common alternative assets such as MLPs, commodities, and hedge funds distribute K-1 income, a special tax categorization that often requires hours of extra work when filing taxes.

Most investors can avoid the worst of these tax concerns by concentrating their less tax-efficient assets into their retirement accounts such as their 401(k) or IRA. Such a practice of Asset Location is as important as it is universally ignored. The basic idea here is pretty simple: many investors have assets in both taxable as well as tax-deferred and/or tax-free retirement accounts. Given that some assets such as common stocks and municipal bonds have favorable tax treatment while others generate more of their returns as ordinary income, it’s generally wise to put more of your tax-efficient assets in your taxable account and less efficient assets in your tax-sheltered accounts. Estimates vary depending on your assumptions about returns, tax rates, and other factors, but even just the simple case of concentrating taxable bonds in a 401(k)/IRA and stocks in a taxable account can add 1% or more a year in after-tax returns compared to an even split. Despite this, most investors seem to ignore the benefits of strategic asset location, generally holding a similar asset allocation in each of their account, including significant allocations of taxable bonds within taxable accounts. Anecdotally, I have even seen this among financial advisors, who will design an asset allocation for a client based on a model portfolio, then go ahead and buy the exact same investments twice or thrice-over for each account, including allocations to highly tax-inefficient assets such as REITs and high yield bonds in taxable accounts, where investors will give away nearly half of their returns to Uncle Sam.

Taxes, for better or worse, make every investor truly unique. The upshot of thinking in terms of after-tax returns is that the same asset allocation is effectively a different portfolio for two investors if they have different tax rates, or different percentages of their assets in taxable vs. tax-sheltered accounts, or even if they bought it at different times (as market fluctuations may present one with tax-loss-harvest opportunities and another with large unrealized capital gains). Said another way, even investors who have the same risk tolerance and the same time horizon may want different portfolios based on their differing tax status. Rules of thumb such as “bonds in an IRA, stocks in a taxable account” may do better than simply divvying it up equally, but once you factor in the real-world complications of including a Roth IRA, considering different asset classes and active strategies, and managing differing cost bases, what is really called for is tax-adjusted portfolio optimization.

As with portfolio optimization in general, the goal of tax-adjusted optimization is to maximize (after-tax) expected return subject to a given level of risk. To do so, expected returns on assets are adjusted based on the taxable liabilities the investor would incur. The component of returns on a stock coming from dividends, for example, may be reduced by the investor’s dividend tax rate. An upshot of this is that the same asset is effectively a different asset in each account it’s invested in (taxable vs. IRA vs. Roth). The optimization then, is done across all the accounts an investor has so as to solve for which combination of assets in which accounts maximizes after-tax wealth.

As you might imagine, the math behind tax-adjusted portfolio optimization is pretty mean. In a later post I will expand upon it and show concrete examples. I find that even controlling for asset allocation, portfolios that are optimized for taxes can deliver substantially better after-tax performance than evenly split portfolios. In my next post, I will continue to explore how individual differences can affect your portfolio and look at how your career, location, and other lifestyle factors might change how you want to invest.

Disclosures: This post is solely for informational purposes. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Investing involves risk and possible loss of principal capital. No advice may be rendered by RHS Financial, LLC unless a client service agreement is in place. Please contact us at your earliest convenience with any questions regarding the content of this post. For actual results that are compared to an index, all material facts relevant to the comparison are disclosed herein and reflect the deduction of advisory fees, brokerage and other commissions and any other expenses paid by RHS Financial, LLC’s clients. An index is a hypothetical portfolio of securities representing a particular market or a segment of it used as indicator of the change in the securities market. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur fees and expenses and cannot be invested in directly.