In my last post I described how the link between risk and return has not been as strong as Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) would predict, and investors willing to use leverage can take advantage of this fact by buying a portfolio of low-risk securities on margin. Indeed, this result was discovered even before the advent of the first index funds, making it something of a wonder that modern finance led to their birth in the first place, which I describe as probably the result of historical accident and organizational expedience.

The nice thing about living here in the future is that we have so much more of the past available to work with. I previously showed the following graph from one of the earliest empirical works in MPT showing the relation between different stocks’ riskiness (measured by beta) and their returns for the period 1931-1965.

The relation is positive, as I noted last time, but too “flat” according to theory. Low-risk securities earn less on average than high-risk securities, but they earn more return per unit of risk, making levered low-volatility strategies attractive.

In their 2013 paper Betting Against Beta Frazzini and Pedersen fill in 52 years of additional data and find the following interesting results:

Over a longer stretch of history, the relation between risk and return has been almost completely flat. In fact, the riskiest stocks have earned some of the lowest long-run returns. This result is corroborated by international evidence, and had actually been known about well before 2013. By the 1980s economists were already growing skeptical of at least the simpler versions of Modern Portfolio Theory. Though the relation between risk and return does explain the differences between major asset classes like stocks, bonds, and cash, beta seemed to explain little or nothing of the difference between individual stocks. What does?

In 1992 Eugene Fama and Ken French wrote what would become one of finance’s most influential papers, proposing a new model of risk and return. Fama was already a highly esteemed academic who in 1970 wrote one of the earliest and most influential papers on the Efficient Market Hypothesis – the idea that managers cannot beat the market by picking better stocks or timing the market’s ups and downs. The new paper presented compelling evidence that a company’s size (measured by market capitalization) and valuation (how cheap its shares were relative to its per-share book value) were key factors in predicting its stock returns. The effects were impressive; from 1926-2012 while the US stock market earned a cumulative annual return of 9.8%, a portfolio of the smallest 30% of stocks earned 11.8%, the 30% cheapest value stocks earned 12.6%, and combining the factors to build a portfolio of small value stocks would have earned 14.6%.

(Source: Ken French’s Data Library)

Almost equally impressive was the irony of the result coming from Gene Fama. Here was an economist famous for advancing the idea that beating the stock market was impossible, now giving a recipe on how to beat the stock market! For his work in both building up and tearing down the Efficient Market Hypothesis, Fama was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics in 2013.

What’s also interesting is how the Fama and French paper brought academic credibility to a very old idea from Wall Street: value investing. In my first post in this series I wrote about how before the advent of Modern Portfolio Theory, Benjamin Graham was one of the first serious thinkers to write about asset pricing. Considered to be the father of value investing, he advocated using measures like the price to book ratio to find stocks that were selling below their intrinsic value. Financial economists, with their assumption of market efficiency, mostly believed this couldn’t possibly work. Now, over half a century later, the data was forcing them to reconsider. (Maybe if they had just listened to Warren Buffett they could have saved themselves a lot of trouble.)

Fama, for his part, has never actually claimed that his results refute the Efficient Market Hypothesis. In his view, small-cap and value stocks aren’t actually undervalued in the sense of being a “better deal.” Rather he believes they are riskier, and that their higher returns are a logical compensation for their risk. It’s just that this risk isn’t captured by the clean statistic of beta.

This sort of makes sense for small company stocks. Small-caps are less liquid and harder and costlier to trade, so it makes sense that they should earn a higher return as a result. Value stocks on the other hand, generally don’t have this problem, plus they tend to actually be less volatile than their more expensive counterparts, and often fall less during recessions/bear markets. The case for the value premium being a risk premium has always struck me as grasping for straws.

One year after the Fama/French small-cap and value paper came out, Jegadeesh and Titman published a paper on a phenomenon called momentum. They found that stocks that had recently outperformed (over the last 3 to 12 months) tended to continue to outperform over the next several months, and similarly underperformers tended to continue underperforming.

(Source: Ken French’s Data Library)

Here risk seems even less likely as a reasonable explanation. Momentum strategies have historically actually been good hedges against bear markets, earning a good chunk of their profits by side-stepping much of the losses that come from market crashes. The fact is not lost on Fama and his fellow efficient marketeers. At a conference shortly after he won his Nobel Prize, I got to attend a Q&A session with Gene Fama. When I asked him what he thought was the most challenging phenomenon to explain in finance, his response: “Momentum.”

Since these early studies, numerous other premium return factors have been discovered. While there is some debate about the statistical reliability of various results, the major factors have been independently confirmed by multiple sources looking at different markets and time periods. As more such discoveries are made, the less “risk” seems like the all-important variable the theorists thought it was.

A Digression on the Folly of Man

Let’s take a step back for a bit here. Why are Fama and the Efficient Markets gang and economists in general so interested in this idea that risk has to be the only thing that explains asset returns? Why shouldn’t other factors like the company’s size or valuation or whether or not the stock has been recently appreciating be part of the explanation?

The reason has to do with a key assumption underlying all of economics: rationality. Economists, whether studying barter economies or stock markets, as a rule assume that the agents involved are rational. My intermediate microeconomics textbook, written by Steven Landsburg, summarized the view nicely:

Economics is one of several sciences that attempt to explain and predict human behavior. It is distinguished from the other behavioral sciences (psychology, anthropology, sociology, and political science) by its emphasis on rational decision making under conditions of scarcity. Economists generally assume that people have well-defined goals and preferences and that they allocate their limited resources so as to maximize their own well-being in accordance with those preferences.

The Swiss economist Bruno Frey put in more pithily in an essay that began with the sentence: “The agent of economic theory is rational, selfish, and his tastes do not change.” When it comes to financial decisions that involve uncertainty, this means that individuals seek to increase their wealth while preferring to avoid risk, and will accurately assess the probability of different outcomes, determine which gambles or investments offer the most attractive tradeoff between risk and reward, and choose those that maximize their happiness (“expected utility” in the language of economists).

If investors all behaved this way, then value stocks shouldn’t earn higher returns on average than the market (assuming they aren’t any riskier) because if they did, then investors would recognize this fact and rationally invest more in value stocks. As more investors did this, prices for value stocks would rise until eventually their expected return no longer exceeded the rest of the market. As a result of everybody rationally optimizing between risk and return, in equilibrium risk should be the only thing that predicts return, because any other pattern would be exploited until it disappeared.

A potential problem with this explanation that may have already occurred to you is that not everybody is always completely rational. But in case your experience as a human being wasn’t enough for this to be obvious to you, in recent decades an entire subfield of research known as Behavioral Economics has sprung up exploring how the decision-making of real-world humans differs from that of the rational-agent model of traditional economics. The founding of behavioral economics is largely accredited to the work of pyschologist Daniel Kahneman and his late colleague Amos Tversky. Kahneman has spent his career conducting groundbreaking experiments in psychology, documenting the numerous ways in which people’s thinking contains errors and biases. His 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow is a magnum opus on the nature of human folly, and for my money one of the most important nonfiction books ever written.

Kahneman’s research began in the early 70s when he and Tversky asked subjects about their preferences regarding different bets. For example, consider the following two offers (taken from Thinking, Fast and Slow):

Problem 1: Which do you choose?

Get $900 for sure OR 90% chance to get $1,000

Problem 2: Which do you choose?

Lose $900 for sure OR 90% chance to lose $1,000

They found that most people preferred the sure thing in the first bet, but were willing to gamble in the second. Rationally, this is inconsistent. A rational economic agent would recognize that the relative attractiveness of the two options is identical and should either choose the gamble or the sure thing in both cases. Whether the outcomes were gains or losses shouldn’t be relevant to the decision. What Kahneman found, across a wide variety of contexts, is that people don’t evaluate consequences based on such absolute notions of utility that exist in a vacuum, but view things relative to some sort of reference point. This should be readily familiar with our own experiences. Consider, for example, a junior level employee making $50,000 that gets a promotion to mid-level and a raise to $100,000. We would expect she would be elated upon hearing the news. Now consider a high-level employee making $200,000 who gets demoted to mid-level with a paycut down to $100,000. We would expect him to be disappointed, if not infuriated, by the news. Objectively, the two employees are now in the same positions and standard economics would hold that they should basically be equally satisfied overall. In reality, of course, the emotions they experience are at polar opposites from one another, because one frames her situation as a gain and the other as a loss. Kahneman refers to this asymmetry as loss aversion.

Over his career Kahneman has identified a laundry list of ways in which people allow emotions or external factors to influence their decision-making in irrational ways. Let me highlight a few examples to give their flavor:

- Anchoring: People unconsciously allow an initial bit of information to influence how they think about a problem, even when the information is clearly irrelevant. In one experiment, Kahneman had subjects spin a roulette wheel. He then asked them how many African nations are in the UN. The answers people gave were highly influenced by the number they had randomly drawn from the wheel. Anchoring effects have been shown to influence bidding prices at auctions, the outcome of contract negotiations and lawsuit settlements, and the amounts customers are willing to spend at restaurants.

- Availability Heuristic: People will overestimate the number or likelihood of something if they can easily think of specific examples. In another of Kahneman’s experiments, subjects were asked “If a random word is taken from an English text, is it more likely that the word starts with a K, or that K is the third letter?” Because it is easy to think of examples of words that start with a K but takes much more effort to come up with examples of words with K as their third letter, participants evaluated the likelihood of the former as much higher. In fact, there are at least twice as many English-language words with K as their third letter than their first. Availability has a huge effect on how people think of risk. People reliably overestimate the likelihood of death by accidents and underestimate the likelihood of death by disease. In polls a majority of Americans regularly reports believing that crime has been going up even though crime has dropped tremendously over the last few decades.

- Overconfidence: People reliably report greater confidence in their abilities or chances than is warranted by their objective accuracy. In one example, when subjects were asked how confident they were that they had spelled a word correctly, those that said they were 100% certain were wrong about 20% of the time. Most people think of themselves as better than average at many tasks, for example, one study found that 93% of Americans think they are better than average drivers. Experts are often overconfident in their field and fail to deliver better judgement than what can be gained by simple formulas. One study found that calculating “frequency of lovemaking minus frequency of quarrels” better predicted marital stability than professional marriage counselors could.

It didn’t take long before researchers realized that these heuristics and biases could have an effect on investment decisions. Indeed, one of the greatest veins of research in behavioral economics has been studying how investors’ choices differ from the rational agent model. A few findings:

- The Disposition Effect: investors are often quick to sell a stock at a gain but hesitant to sell at a loss. Even though a stock doesn’t know about an investor’s profit & loss statement and it should have no effect on its future returns (and tax consequences should favor the opposite behavior) investors’ loss aversion often makes them reluctant to realize a negative outcome.

- Naive Extrapolation: Investors often favor stocks of companies that have recently experienced rapid earnings growth, believing fast-growing companies will continue to grow quickly while companies with slow-growing or shrinking profits will continue to lose ground. In reality, recent earnings growth gives almost no indication of future earnings growth. Investors are anchoring on irrelevant information.

- An effect of overconfidence: investors often underestimate the risk of their portfolio and overestimate its expected return. Investors that are the most optimistic about their ability to do well trade the most, earnings lower returns after fees.

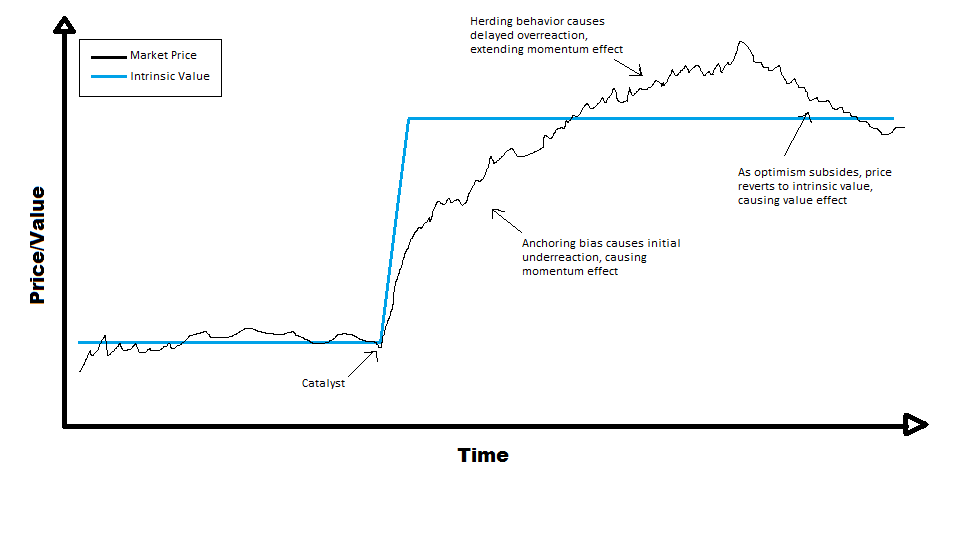

If investors succumb to these sorts of biases en masse then their actions could push asset prices away from their rational values determined by risk, and give rise to predictable return patterns. Indeed, a literature exists seeking to explain how various cognitive biases relate to return factors that have been observed in the market. One widely cited theory is initial underreaction and delayed overreaction: the graphic below illustrates the idea; suppose an event happens that changes the rational, intrinsic of a company, such as a positive earnings announcement. While the price rapidly increases towards the new intrinsic value, an anchoring bias among investors leads them to update more slowly than they should, causing the price to drift upward gradually and predictably – the momentum effect – as the price continues to rise, herd behavior and availability bias lead investors to believe the stock will only continue to go up, causing them to bid the price up even further, overshooting its fundamental value. Eventually, the now-overvalued stock’s price falls back towards its fundamental value – the value effect – either because rational investors sell out or because incoming news disappoints the optimistic herd-traders.

With behavioral economics, the market is no longer the efficient, rational machine of Modern Portfolio Theory, but more like the manic-depressive Mr. Market of Benjamin Graham’s old analogy, often offering to buy or sell shares at prices that have more to do with his emotional state than any objective truth.

So why hasn’t the notion of rational economic actors been discarded into the dustbin of history along with the notion of efficient markets? Economics does have a standard response to the criticism that the rationality assumption is unrealistic. Landsburg again:

Students are sometimes uncomfortable with the assumption of universal rationality. Often they point out that the assumption is clearly false, and they are surprised that their economics professors don’t seem particularly concerned about this. But the fact of the matter is that all assumptions made in all sciences are clearly false. Physicists, the most successful of scientists, routinely assume that the table is frictionless when called upon to model the motions of billiard balls. They assume that the billiard balls themselves are solid objects. They assume that objects fall in vacuums. They study the behavior of electric charges that are localized at mathematical points and that interact only with a small number of other changes, as if the rest of the universe did not exist.

All scientists make simplifying assumptions about the world, because the world itself is too complicated to study. All such assumptions are equally false, but not all such assumptions are equally valuable. Certain kinds of assumptions lead consistently to results that are interesting, nonobvious, and at some level testable and verifiable.

In other words, the assumption of rationality was never meant to be a true statement about the human mind, but is simply a useful contrivance for generating predictions. He continues:

The rationality assumption in economics continues to disturb some students at a far more visceral level than the frictionless planes that other sciences assume. It seems plausible that a world without friction could resemble our own world in important ways, but students find it much more difficult to believe that the behavior of perfectly rational individuals could bear much resemblance to the behavior of the people they encounter in their everyday life… It is a misconception, however, to believe that a world in which most people are irrational would have to function very differently from a world in which everyone is rational. Imagine a world in which most people are irrational most of the time, but where enough people are rational enough of the time so that there are no unexploited profit opportunities. Such a world would function very similarly to one in which everyone is rational.

So even if most investors make irrational investment decisions, as long as there are enough rational money managers around competition among them should drive out “unexploited profit opportunities.” You probably recognize the problem here: the persistence of the value and momentum effects and other return patterns suggest that there are unexploited profit opportunities, just waiting for intrepid, rational investors to scoop up. This gets to a common reaction people have upon hearing about the value and momentum effects: if these strategies are so great, why don’t more people use them? Why wouldn’t competition among rational investors drive out these premiums, and why should we expect them to persist?

Adaptive Markets

In my view the reason why these irrational pricing effects have happened in the past and are likely to continue in the future is a concept known as the limits of arbitrage. The profits from a strategy such as value investing are not guaranteed or risk-free. An undervalued stock may become even more undervalued after an investor purchases it. It may take several years before its price reverts to its “true” intrinsic value, and the investor may not be able to wait that long, especially if he is investing on behalf of others. Most of the world’s investment wealth is managed by financial professionals on behalf of nonfinancial experts. Though many of the former may be quite knowledgeable about statistics, portfolio theory, and behavioral economics, their clients won’t necessarily be as informed, and are likely to hire or fire their money managers based on spurious short-term performance. Whether it’s individual investors picking mutual funds or the plan sponsors of pensions, foundations, and other investment pools picking institutional managers, investors typically judge manager performance based on relatively short time horizons of 3-5 years or less, a period over which even a fundamentally solid strategy can underperform just by bad luck.

Rather than viewing the market as a place where all investors have perfectly calibrated beliefs and unlimited capital at their disposal, jumping instantly on any mispricing until risk and return are balanced out, it is better understood as an environment where different actors have varying degrees of understanding and access to capital. These different sorts of actors interact with each other in interesting ways that may cause mispricings to ebb and flow in the market. Consider the case of the value investor: as I wrote about recently, value strategies have generally underperformed for going on a decade now. As I wrote in that post, I believe this is not evidence that the value premium has disappeared, but in fact that it is likely to be higher than average in the intermediate future. But consider some stylized examples of how this spate of bad luck impacts different investors:

- A hyper-rational hedge fund manager that manages her own money. She has perfectly calibrated estimates of the expected return and risk of all assets and constructs her portfolio by overweighting undervalued securities and short-selling overvalued ones, using significant amounts of leverage to maximize the expected geometric growth rate of her portfolio. She is as close to the economist’s ideal investor as possible, short of only the fact that she needs a real-world broker to provide her margin loans, which may require varying amounts of collateral as macroeconomic conditions change. She rationally estimates that there is a 2% chance that adverse market conditions may result in a margin call forcing her to liquidate her positions at great loss, and she accepts this risk. As value stocks suffer a bad streak by chance, her portfolio is squeezed and she is forced to sell some of her assets to post margin. Unfortunately, a bunch of other rational hedge-fund managers with similar portfolios are all in the same positions and they all sell at the same time, pushing prices on the undervalued securities lower and overvalued securities higher in a classic liquidity crisis. She is therefore forced out of her portfolio even as its expected return is going up. (It’s believed that something just like this happened in August 2007, around when value strategies began their recent doldrums.)

- A rational portfolio manager who manages money for pensions, foundations, and high-net-worth-individuals. He has been a value investor with a successful track record which he has let speak for itself when taking on new clients. Unfortunately, he hasn’t spent much time on client education so most of his clients don’t really understand why he has been successful and have basically just assumed he was a competent professional, and that like competent professionals in most other fields he would perform consistently well. As value stocks deteriorate and then crash following a hedge fund driven liquidity crisis, his performance suffers compared to his benchmark. Some of his newer clients who haven’t been with him long bail immediately. Many of his established clients put him “on watch” and stop allocating additional funds to him. The net result is that as clients leave, more value stocks are sold than bought, making them even cheaper.

- An intelligent financial advisor who learned about market efficiency, value investing, and all that in business school 20 years ago, but now spends most of her professional time on building client relationships and other aspects of the business than portfolio management. She keeps her portfolios relatively simple, using a handful of value-oriented mutual funds, which have been successful more often than not. Now value has underperformed for a few years in a row and some clients are starting to complain. Some of them ask why they are paying extra fees when index funds would have done better. After doing a few hours of research, she becomes more convinced by the fact that Vanguard has outperformed most of her funds recently and at lower costs, and decides to switch her clients over to index funds, selling value stocks and making them even cheaper.

- An overconfident broker working at a traditional Wall Street broker-dealer. He has little formal training in economics beyond what was necessary to get his securities license and has never heard of Daniel Kahneman. He’s distrustful of academic theories on the market and says “sometimes you just gotta go with your gut.” Charming and extroverted, he is a good storyteller and active in his community. Most of his clients use him because they think he’s trustworthy and “tells it like it is.” Most of his research consists of listening to the news and looking at performance charts. He trades his accounts often as he learns about new “themes” and isn’t afraid to make big bets. A few of his calls paid off big over the years, and though most economists would say he was probably just lucky, he and his clients take it as a sign he’s a skillful trader. Value has underperformed for nearly a decade now, and he declares “Value is dead; the economy is a different place than it was 30 years ago, we gotta adapt and invest in the areas that are gonna add growth.” He sells any remaining value stocks and funds he has and buys mostly web service and biotech stocks that have been outperforming for three or four years now.

What we see across these scenarios is that market competition does not necessarily cause an inevitable march towards efficiency, but rather there is an ecosystem where rational and irrational forces buffet prices around. Some researchers have taken the ecosystem metaphor seriously and begun to use principles from evolutionary biology to try to understand the financial markets. The Adaptive Market Hypothesis states that the marketplace is like a shifting landscape in which organisms compete for food and evolve. Certain investment strategies may work in certain environments, then may attract competition, become overexploited, and cease to work, causing “extinction” as investors lose clients and are forced out of the market, perhaps allowing the strategy to flourish again in a repeating cycle. Investors use limited cognitive resources to try to identify valuable sources of return and the key to survival is the ability to adapt – and to be able to go hungry for a while without dying.

In his book Efficiently Inefficient, Lasse Pedersen makes the point nicely:

Markets constantly evolve and gravitate toward an efficient level of inefficiency, just as nature evolves according to Darwin’s principle of survival of the fittest. The traditional economic notion of perfect market efficiency corresponds to a view that nature reaches an equilibrium of “perfectly fit” species that cease to evolve. However, in nature there is not a single life form that is the fittest, nor is every life form that has survived to date “perfectly fit.” Similarly, in financial markets, there are several types of investors and strategies that survive and, while market forces tend to push prices toward their efficient levels, market conditions continually evolve as news arrives and supply-and-demand shocks continue to affect prices.

So will the premiums to value, momentum, and other strategies be as high in the future as they were in the past? Probably not. As the premium return factors have become more well-known more investors are trying to exploit them and now many asset managers offer easy, bundled access to them. Though overcrowding may lead to extinction events like the kind I portrayed above which periodically give rise to attractive opportunities (as I believe is now the case with value stocks), in general we should expect profit opportunities to diminish as investors become more sophisticated over time. But to the extent that investors are human beings who sometimes reason with their emotions, who tend to follow the herd and who are prone to impatience, loss aversion, anchoring and other biases, we should expect more reasonable investors who have a systematic process that they’re willing to stick with for the long term (sometimes through ten years or more of underperformance even) to be rewarded for making the market a little less crazy.

Much of what I have said in this post is controversial to some extent. Academics and practitioners debate the ideas of market efficiency and investor behavior constantly and there is nothing close to a consensus on the matter. I think the idea of adaptive markets highlights the idea that consensus in fact is impossible, because if one existed, it would sow the seeds of its own destruction. Asset pricing is an inherently uncertain occupation. Next time, we will shift gears a bit and talk about one of life’s only certainties: taxes, and how they affect investment decision-making.